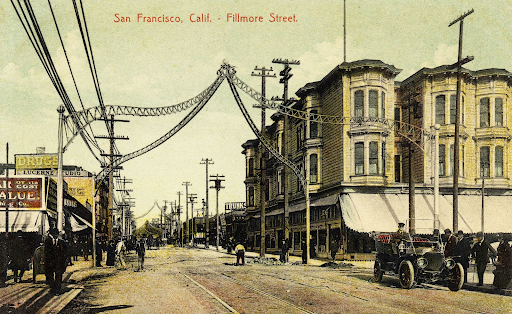

The Fillmore included a large number of Jewish bakeries, markets, restaurants, butchers, bookstores, and other businesses, and was a destination for Jews from throughout the city. The epicenter was McAllister Street. Here is a description from the 1930s WPA Guide to the City by the Bay by the Federal Writers Project:

“Near the southern end of Fillmore Street’s lengthy market place, where its noisy turbulence give way again to prosaic respectability at the foot of another hill clustered with turrets, bay windows, and mansard roofs, lies the city’s Jewish commercial center, the heart of the before-the-fire section, where bedizened old houses of the 1880s advertise housekeeping rooms on grimy signs. Yet, paradoxically, here is a gourmet’s paradise; along adjacent blocks of Golden Gate Avenue and McAllister Street the atmosphere is spicy with the odors of delicatessen shops, bakeries, and restaurants. In a dozen strange tongues, bargaining goes on along McAllister Street… Gathered in this district are a large number of the city’s 30,000 Jews, most of them immigrants from eastern Europe, many being recent arrivals.”

Although the area described above was later bulldozed, several notable Jewish sites from the past do remain in the Fillmore. Most prominent is the former home of the Hebrew Free Loan and Jewish Educational Society at Buchanan and Grove Streets, built in 1926. This is where the community’s Central Hebrew School met, led by Rabbi David Stolper. It is today a Korean community center.

A Home for Many Ethnic Groups

After the war, about half of Japantown’s former residents were able to return, and the community soon regained much of its size. However, a subsequent wave of redevelopment would take away many of their homes and businesses.

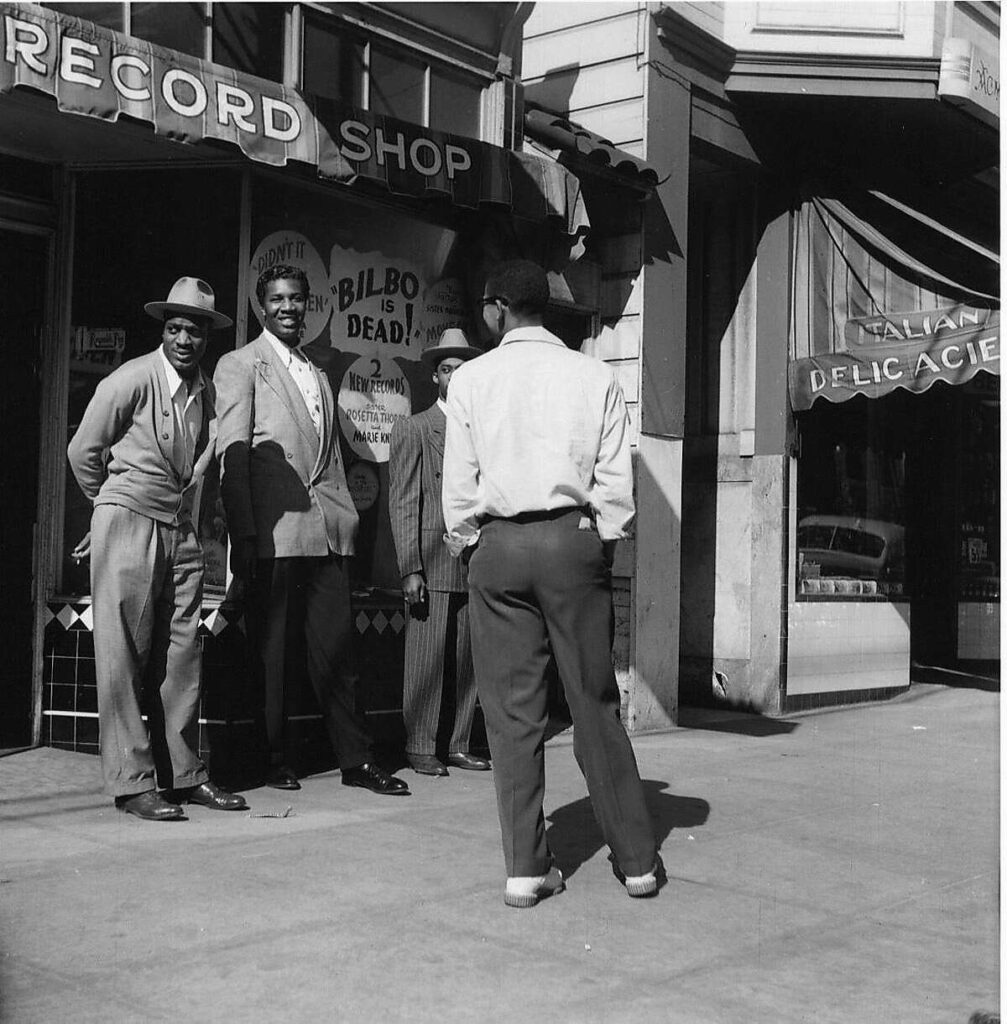

Black San Franciscans had been in the Fillmore since the turn of the century, but not in great numbers. Before World War II the city had fewer than 5,000 Black residents, and slightly fewer than half lived in the Fillmore. But the war changed everything, with people arriving both for wartime jobs and for a way out of the Jim Crow South. While the jobs were plentiful, so was housing discrimination. The Western Addition, which had long been ethnically diverse, was more hospitable than most other neighborhoods to Black housing applicants. Additionally, the absence of Japanese American residents after February 1942 meant the sudden availability of a vast number of vacant apartments and storefronts. Between 1940 and 1950, the Black population of the Western Addition went from just over 2,000 to nearly 15,000.

Maya Angelou, who lived in what had been Japantown as a teenager, portrayed the area’s transformation in her book I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings:

“The Yamamoto Sea Food Market quietly became Sammy’s Shoe Shine Parlor and Smoke Shop. Yashigira’s Hardware metamorphosed into La Salon de Beauté owned by Miss Clorinda Jackson. The Japanese shops which sold products to Nisei customers were taken over by enterprising Negro businessmen, and in less than a year became permanent homes away from home for the newly arrived Southern blacks. Where the aromas of tempura, raw fish, and cha had dominated, the aroma of chitlings, greens and ham hocks now prevailed.”

Redevelopment

“In view of the characteristically low incomes of colored and foreign-born families, only a relatively small proportion of them may be expected to be in a position to occupy quarters in the new development.”

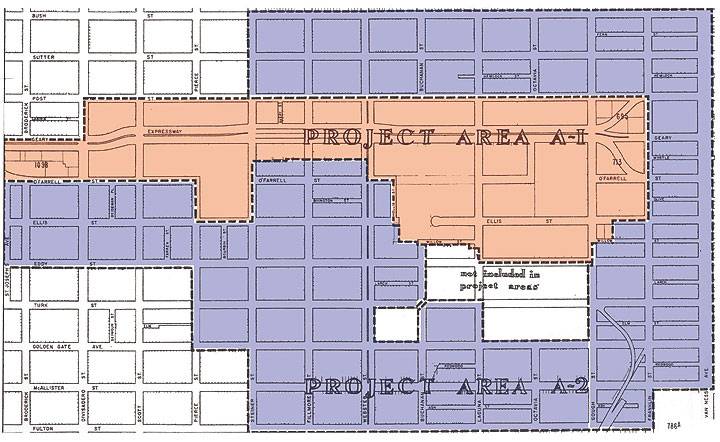

In June 1948, the Board of Supervisors declared the Western Addition a blighted area and designated it for redevelopment, creating the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency to do so. With the passage of the Housing Act of 1949, the federal government would pay two-thirds of the costs of “renewing” blighted areas. And cities could pay their share in credits achieved through public improvements, rather than in cash.

The city’s plans were enacted in two phases. The A-1 area, approved in 1956, had two primary objectives. The first was to transfer more than a mile of Geary Street into an expressway, expanding it from four lanes to eight lanes in order to facilitate the movement of traffic between the Richmond District and downtown. The second was to demolish most of Japantown, replacing it with a new shopping center on the west and with luxury apartment buildings on the east side.

A-2, which was approved in 1964, covered a much larger area, including the rest of Japantown. It sought to remove nearly all of the housing in the Lower Fillmore and create a new commercial strip along Fillmore Street.

It took a long time. The picture on the right from the 1970s (with the Jewish Community Library’s parking garage at the bottom) shows some of the cleared blocks that would remain vacant for more than a decade before work on the Fillmore Center started.

The area’s development resulted in the destruction of thousands of Victorian homes, whose architectural style was not valued as it is today. At the end of the redevelopment era, opposition to the wholesale destruction grew among preservationists. The Redevelopment Agency allowed for the possibility of relocating some of the few remaining Victorians if prospective buyers would assume the cost of moving them. The two blocks to the west of the Library has the city’s highest concentration of moved buildings. The photograph on the right, taken by Dave Glass in 1976, shows two Victorians that have been moved about a mile to an already bulldozed block. These buildings are visible today a half block west of the Library on Ellis Street (see lower photograph). Many of the buildings facing the Library on Scott Street, and most of those on the north side of Ellis between Scott and Divisadero Streets, were moved from other parts of the Western Addition. The buildings were dropped onto vacant lots that, ironically, had themselves been the sites of destroyed Victorian era homes.

Conclusion

In spite of its challenges, the neighborhood surrounding the Library remains a vibrant one, with nightly concerts a few blocks away at the Fillmore Auditorium and Sheba Lounge; such culinary destinations Jane the Bakery and State Bird Provisions; and baseball, soccer, lacrosse, and swimming at the Hamilton Recreation Center. Just six blocks from the Library are the bustling Divisadero corridor and the Upper Fillmore shopping area. We at the Jewish Community Library are proud to be part of a multicultural neighborhood with a rich history.